retro-spectives

Monday Reports

Szan Tan / National Museum of Singapore

13 January 2014

Szan Tan, Curator, National Museum of Singapore

Founded in 1887, the National Museum of Singapore is the oldest museum in Singapore. It houses the permanent Singapore History Gallery and Singapore Living Galleries, and various temporary exhibitions. The current and most recent exhibition is A Changed World: Singapore Art 1950s-1970s, which examines the development of local art made in post-war Singapore.

In the case of curating an exhibition, research is essential. I suppose it's particularly important if everything you present, every decision you make, affects how the public is going to view history (or whatever topic is being presented.) Research informs every aspect of the curatorial process.

Szan shared that an exhibition starts off with an idea of a general topic; in this case she and her team started off with wanting to do "Art & Nation(-building)". After several rounds of brainstorming, they settled on the concept of "A Changed World", particularly since the exhibition coincides with the Singapore Biennale's theme, If The World Changed. This led to an initial survey of available artefacts, which had to be individually and collectively researched. Collectively, the time frame, geographical extent and context had to be researched in order to establish a criteria for artifact selection, which obviously affects the cohesiveness of the exhibition. Individual artifacts had to be researched for provenance; its author (or artist in this case) and story also shed light on art during a changing Singapore. This also helped to uncover artist groups (like the Ten-Men Art Group) and local styles (the Nanyang Style) during that time.

These research later influenced the exhibition design; for example, as Szan shares, plywood was used as it was an emerging material during the '50s. The art catalogues that were used for reference were also displayed on a clipboard - conjuring an image of a street-sketching artist - for visitors to view. The concept of change and development was reflected in the layout of the space itself; when the visitor walks through the aisle, he is confronted with Abstraction on one side, and Realism on the other. Szan said that this was done on purpose to juxtapose the different styles that emerged during that period.

The above artwork is one that I personally liked, Building an Oil Rig (1976) by Ong Kim Seng. Used to seeing watercolours of landscapes, streets and people, this painting surprised me with its unconventional subject matter (in my opinion anyway). To me, watercolour always renders the subject in a soft, pastel, dreamy feeling. To see a construction site painted in such a way made me pause to admire it. It's this clash of subject matter and style that interested me (I've always been quite fascinated with unconventional hybrids), and made me ponder what the artist felt as he was painting it. Was he looking at these developments as a good thing, as hope for Singapore's future? The oil rig rises up in glory in the middle of the frame, almost reminiscent of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.Nowadays, construction sites have become a symbol of the nation's mad frenzy for 'development', the salt rubbing into the wound of a fast-paced lifestyle. People question, "At what cost?", then sigh in resignation and shrug their shoulders when they realize there is nothing they can do about it. The scene in the painting could well be a scene from today, but will any watercolour artist today paint such a scene? There's plenty of street scenes, but not many (none that I've seen at least) of construction sites. Because really, who wants to paint these scenes that have become so commonplace in our lives, that represent loss (of what that spot used to be, of what the building was previously) more than the hope it was 38 years ago? (And well that's related to my final year project topic, so perhaps I am overly sensitive towards such issues!)

I also really liked Still Life (undated) by Qwek Wee Chew, because of the obvious hybrid of Western and Eastern styles. The fruits look so very Chinese, especially the stalks. They look like they were painted on in ink on Chinese paper, instead of oil and canvas. One of my design interests is how to incorporate Western styles into Eastern design (and vice versa), so this painting in particular appealed to me. I was - indeed - mildly and pleasantly surprised that people have already been tackling such an issue years ago.

Darryl & Basit / Terrain

21 January 2014

Darryl Lim and Abdul Basit Khan, Terrain: Office for Research and Design

Darryl and Basit form the two-man team of Terrain: Office for Research and Design, though they mentioned that they used to take on interns and do collaborations now instead. Having met in LaSalle College of the Arts, the two went on to work in various design agencies, publishing houses and schools before setting up Terrain over a cup of coffee. Whilst they each have their own design strengths, the company focuses on Branding and what they call Information Design (which basically encapsulates all the other collaterals from brochures, posters and publications, to wayfinding and websites.)

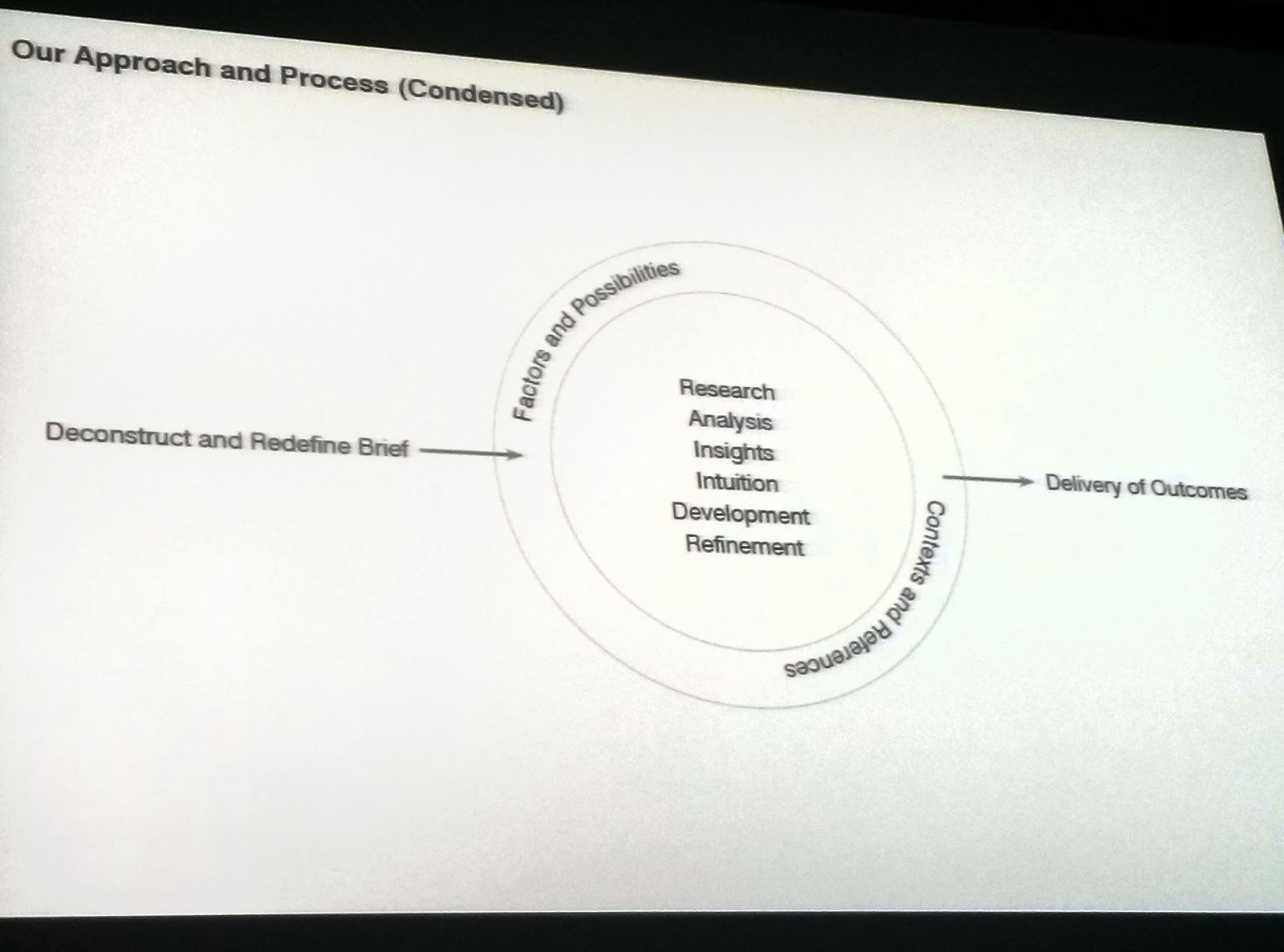

At the start of the presentation, they made a disclaimer: They were not going to talk about research. Instead, they shared with us their beliefs of the design process, and how it works for them. Here is a chart of their design process:

Although they didn't talk much about their methods of research, they gave examples in their portfolio. When they spoke about the design decisions they made (e.g. the typeface or colour), their choice was consciously (or sometimes unconsciously) influenced by the research into the brief. One example was using the typeface Univers in the catalogue for A Changed World, which they said was chosen because it was often used in the publication designs during the '50-70s.One thing that Darryl & Basit talked about was 'intuition'. When do you stop researching, and let intuition take over? They gave us a quote from an interview with Brian Boylan, the CEO of Wolff Olins:

Our process is about getting a deep understanging of our clients, which which is why we have people who come from a more strategic and business background. But then we start exploring, and that's where the intuition comes in. All in all, from the beginning to end, it's a creative process, as opposed to a step-by-step logical process. Because if you only followed a logical process you'd inevitably arrive at a dry answer. Some of the answers we arrive at are beyond logical processes.

Because I am, at the time of writing this, somewhat stuck between the stages of research and intuition, it struck a chord with me. Sometimes we just have to stop thinking (logically) so much, and let our minds go wild on ideas. Or let ourselves think about something else and hope that doing so will suddenly connect the dots for you. To me, that's what 'thinking out of the box' (the much hated phrase in GSAofS) is about; it's keeping yourself from thinking about the brief so much that you corner yourself with your own thinking. It's limiting your options. To think out of the box is, perhaps, to let intuition step in.

Jay / RSP Architects Planners & Engineers

27 January 2014

Tsai Chung Jay, Deputy General Manager of RSP Architects (Shanghai) and Architect

Jay - apparently an alumni of GSA! - came to speak to us today, and enlightened us all on the tedious, thorough process of urban planning. I never knew how much work went into planning a city, and I personally think urban planners must be perfectionist and OCD-types, to go into such a level of detail that the average person would think is important. I refer particularly to the fact that a city skyline is actually designed. And here I was, thinking that it just happens by itself - buildings and skyscrapers just get built and eventually forms a skyline. But nooooo, apparently there are people who plan them.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let me start from the top.

Jay started off with an introduction of what a planner does ("make assumptions"), which is based on research and analysis. Research involves studying land use, population, et cetera, which is then compiled into a 'master data' spreadsheet (which is also filed away for future reference). Another big part of their project research is case studies, whereby similar spaces around the world is referenced, and used to 'inspire' (in our terms; I'm pretty sure they have a proper term for this) the project. These case studies can be very broad (land use in a CBD), or more specific (the location of cruise terminals) depending on the project.

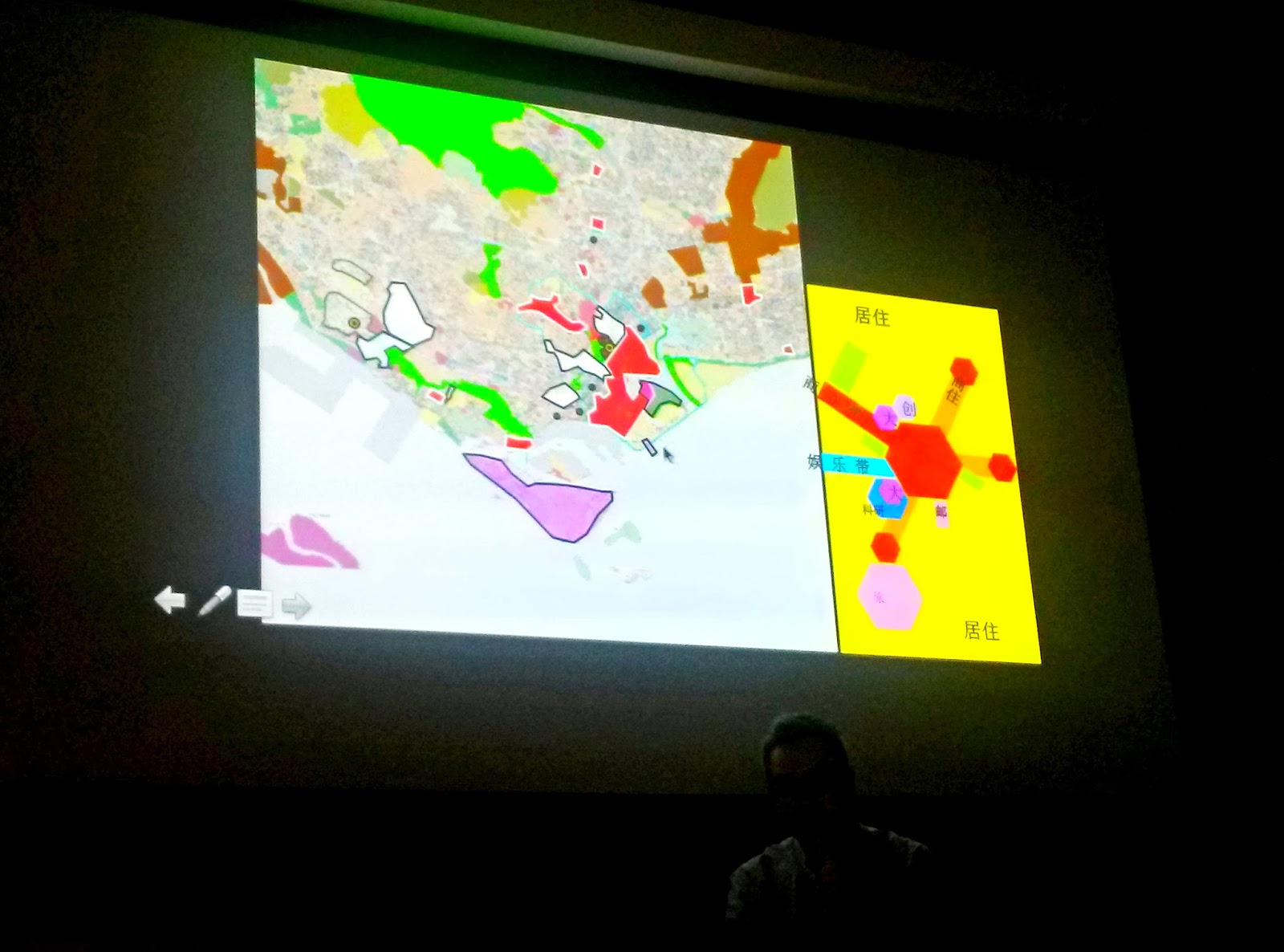

Jay showed us a few case studies and how these data can be represented in diagrams. I'm sure it wasn't his main intention, but I was fascinated by the land use diagrams which are, essentially, infographics. In this picture, Jay was talking about land use in Singapore's city district, with the CBD in the core (red hexagon), Orchard Road and its commercial businesses offshooting to the left, and other land used for entertainment, F&B, arts etc. What's cool is not only the colour code or size of each hexagon, it's also based on location. While it's not exactly geographically accurate, the direction in which the long rectangles branch out of gives an indication of their relative orientation and distance from the core CBD. For example, the big pink hexagon at the bottom represents Sentosa, as seen in the map. I thought these unintentional infographics (or as Jay calls them, diagrams) were really cool.

Jay showed us a few case studies and how these data can be represented in diagrams. I'm sure it wasn't his main intention, but I was fascinated by the land use diagrams which are, essentially, infographics. In this picture, Jay was talking about land use in Singapore's city district, with the CBD in the core (red hexagon), Orchard Road and its commercial businesses offshooting to the left, and other land used for entertainment, F&B, arts etc. What's cool is not only the colour code or size of each hexagon, it's also based on location. While it's not exactly geographically accurate, the direction in which the long rectangles branch out of gives an indication of their relative orientation and distance from the core CBD. For example, the big pink hexagon at the bottom represents Sentosa, as seen in the map. I thought these unintentional infographics (or as Jay calls them, diagrams) were really cool.

He then took us through the entire planning process by showing us some existing projects; the research is really very very very detailed and thorough, and this is where I was enlightened about designed-skylines. I suppose research is important in planning a space that is to be inhabited by so many people. Only after today have I realised that all the built environment around us were planned by someone(s) somewhere sometime ago, and this realisation is both startling and scary at the same time. It feels like the my life has been dictated and controlled by some city planner, yet I'm also awe-struck at how all the subtle nuances of our built environment (like skylines) were actually taken into consideration by someone, which sometimes even affects our lives. I thought of Le Corbusier and his grid-system-cities, and remembered how I got lost in Taiwan because two roads which I thought would intersect at the next junction did not. Because it wasn't a planned grid system, but a series of winding roads.

Of course, grid systems aren't the best solution for every city in the world, and that can only be concluded when one has done his research. After today, I have a newfound respect for these space planners who put so much effort into research and details, so that the best plan can be produced. It's kind of like user-centred design, now that I think of it.

Jean-Marc Gauthier

10 February 2014

Jean-Marc Gauthier, Associate Arts Professor at Tisch School of the Arts Asia, animator, architect, author, entrepreneur, interactive designer

Jean-Marc's website is such an appropriate title for him - tinkering.net. He gives me the impression that he tinkers in many things (just look at his many designations) and his lecture did reflect his knowledge in many areas including those outside of design.

Jean-Marc's website is such an appropriate title for him - tinkering.net. He gives me the impression that he tinkers in many things (just look at his many designations) and his lecture did reflect his knowledge in many areas including those outside of design.

Initially trained as an architect, Jean-Marc later went into the world of 3D animation and virtual interaction, studying at Tisch School of the Arts New York. He now teaches at its Singapore branch, chairing the Animation and Digital Arts programme.

As a researcher himself, he gave us very practical advice on how to tackle the research process. The first piece of advice he gave when he started was that research can take place during your 'off-hours' (after asking us if we remember and record our dreams down). I found myself nodding in agreement. Good ideas have often come to me whilst on the bus ride home, or in the shower. The key is to do your research, then take time off instead of trying to force something out from the research. I read a similar article on brainpickings.org a while ago called A 5-Step Technique for Producing Ideas, where Step 3 was 'Unconscious Processing'. But on the other hand, Jean-Marc also cautions, research is "a challenge you give yourself, and it takes effort." Reflecting on how I've viewed the research process in polytechnic and in university, I find that it's easy to do surface research. The basics of company profile, target audience, styling and mood, et cetera. But it really takes effort for one to go beyond that, dig deeper, and challenge oneself to read up on difficult things - philosophy, mathematics, mechanics, social constructs, psychology. Many professional designers also give similar advice - read a lot and be curious.

Moving on, Jean-Marc gave us 10 pointers to aid the research process, although he didn't have time to go through all of them. The ones he did go through were:

1. You and the Others (the people around you; he mentions the 6 degrees of separation.)

2. Motivation (even if you're motivated due to frustration or as an reaction.)

..

4. Sometimes it works, sometimes it does not (I particularly liked the quote he put on the slide about Poincare, very poetic - An idea is "lightning in the depth if the night that we remember about.")

5. Balance the unconscious/conscious intellectual (Respect your mind! Don't stretch it beyond what it can take, but don't underestimate it either.)

6. Luck (which, in his definition, is something for which we create the conditions of. We can decide how 'lucky' we are.)

7. Know how to rebound (in other words, be flexible and work around the problems that come along.)

..

9. Create the environment of your research

..

Scott Maguire / Dyson

18 February 2014

Scott Maguire / Head of something at Dyson (he didn't tell us exactly what his designation was...)

The last guest lecture was given by Scott Maguire from Dyson, the product design and technology company famous for their vacuum cleaners and bladeless fans.

The last guest lecture was given by Scott Maguire from Dyson, the product design and technology company famous for their vacuum cleaners and bladeless fans.

The company was founded in 1993 by Sir James Dyson, who started on this path of inventing when he got frustrated at the numerous problems caused by the wheel of a wheelbarrow. He replaced it with a ball, and even won some awards for it. Then in the 1970s, he found himself troubled by the problems of another household appliance - a Hoover bag vacuum cleaner. This eventually led to the invention of Dual Cyclone bagless vacuum cleaner that kick started the company, and of which it is famous for now.

The creative process behind the vacuum cleaner apparently shapes the research & development process at Dyson. Scott shared with us the five main mindsets that guide their approach to product development:

-

Frustration

-

Wrong Thinking

-

Perseverance

-

Underdog

-

Perfectionism

I found them all very relevant, things that I myself have encountered once before, or ways of thinking that shape my own design process. Funny how a talk on industrial design ended up the most interesting and relevant, but I've always been interested in how product designers think. I have a few friends who study/studied product or industrial design, and I'm always fascinated and awe-struck when I see their sketchbooks, or hear them chart out their thought process.

The sketchbooks, because of their ability (habit?) to just sketch as many forms and ideas as possible. James Dyson apparently made 5127 prototypes of the abovementioned vacuum cleaner before developing the final one. The thought process, because they are really observers of human behaviour, more so than - I would say - us graphic designers, photographers or illustrators. Somehow, product designers (the ones I know anyway) are able to delve to the root of the problem and pinpoint the core need of the consumer, and that always shapes the way they approach the brief. The way they ask questions about these needs are also very different from the way I've been taught to look at design problems. All in all, I have a good measure of respect for industrial designers and the way they think, which is something I've been trying to understand. Today, Scott broke this process/approach - in Dyson at least; but look how good they are, they must be doing it right! - down to 5 points and it turns out I knew them all along, albeit a little differently, or had problems 'implementing' it in my own design process.

'Frustration' is something that I'm feeling at this point of the final year project, where I'm stuck and don't know how to move forward. 'Frustration' is often thought of as negative, but at Dyson, as Scott explains, it is harnessed to propel you to find a solution. The more frustrated you are, the more you are driven to do it better. Well he was referring to frustration with existing problems (such as the wheelbarrow), but it changed my perspective. Every negative problem that comes along during a project can be turned around into a positive motivation. Which leads to the other few points that Scott spoke about - Wrong Thinking and Perseverance. Sometimes the oddest ideas can be the best ideas, and perseverance is obviously a crucial factor for dealing with frustrating problems that don't seem to have a solution, and also for pushing an idea that everyone else discounts.

This radical way of looking at things is what made Dyson the number one brand in a few markets, and their work approach and culture can be summed up in a quote Scott gave (which he said was James Dyson's favourite):

I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work.

- Thomas A. Edison

This is reflected in the 5127 prototypes James Dyson made. Scott also said, "If you don't fail, you're not creating something."

At the moment I'm pretty down in the dumps over the way my project isn't working according to what I expected. Time for me to pick myself up, and push on with my project!